At Daytona International Speedway, if you see a silver wheelchair-accessible minivan flash by outside the stadium, it’s shuttling people who need assistance getting around the expansive venue. Philip James “PJ” Nicholoff would be happy knowing that his family donated his beloved van to the speedway, and its back windows display signage honoring him.

A big NASCAR fan, PJ lived with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) for 31 years. He may no longer be driving that van, but his father, Brian, proudly proclaims that “PJ drives on” with the medical-care guidelines he inspired: the PJ Nicholoff Steroid Protocol.

The guide that saves lives

Long-term corticosteroid treatment, which is common for DMD and Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD), leads to adrenal suppression, meaning the body is unable to produce enough cortisol on its own. In this case, rapid reduction or withdrawal of corticosteroids can lead to life-threatening complications.

The six-page PJ’s Protocol, as it’s commonly called, outlines procedures that healthcare providers should follow for patients who depend on corticosteroids. It explains how to safely manage corticosteroid treatment for them in emergency situations. It also points out the signs and symptoms of acute adrenal crisis (when cortisol plunges to life-threatening levels), how to prevent this by giving stress (extra) doses of corticosteroids, and how to taper those extra doses off to avoid dangerous withdrawal.

Whether the protocol is in a medical facility’s care guidelines, the hands of a parent arriving with their child at the ER, or a patient’s electronic health record, it equips families to advocate for proper care for their loved one. It also aims to ensure that no one else goes through what PJ and his family did.

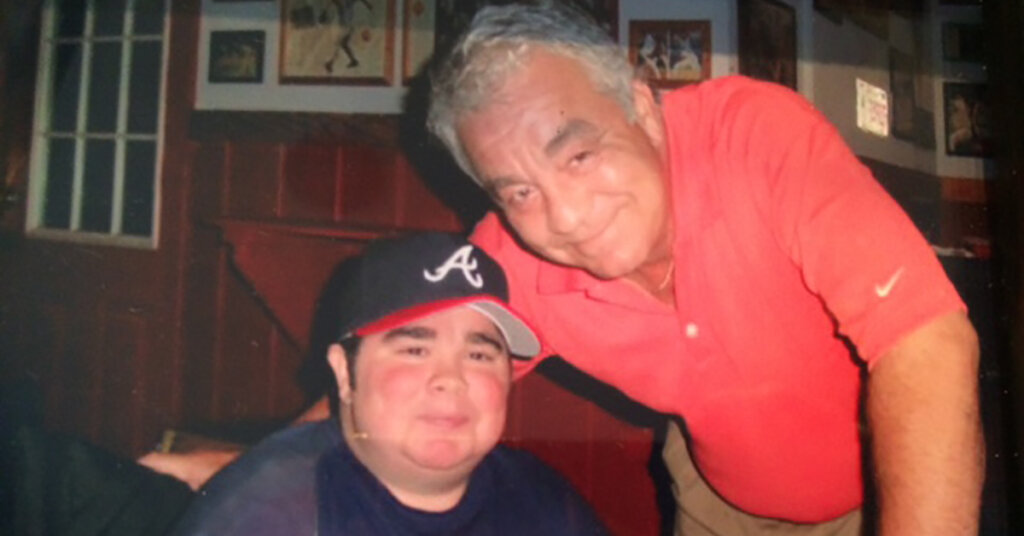

A treasured life

First diagnosed with DMD at age 4, PJ started a corticosteroid two years later and was on it for the next 25 years. “It delayed the progression of the disease for several years. But, eventually, he experienced common adverse side effects of weight gain, cataracts, kidney stones, and mood swings,” Brian says. “The biggest one is osteoporosis. During PJ’s teenage years, before using a wheelchair, he broke his femur, hips, and ankles in falls. Each one took him down a little more, and then he could no longer walk.”

In 2013, while the family was in Florida, PJ fell from his wheelchair trying to make it to the bed. “I saw that his legs were crossed underneath him and that he had fractured his hip and also his humerus,” Brian recalls.

They wanted PJ to be closer to their home in Indianapolis, so he was flown to a hospital there for emergency orthopedic surgery. It was successful. Soon after, though, his lungs filled with fluid, his heart raced at over 100 beats per minute, and his blood pressure plummeted. Six days later, he died.

“We’ll never know for sure what happened,” says Brian. “On the day of PJ’s surgery, he was given the correct dose of steroids. But a review of his medical records three months later showed that afterward, while he was hospitalized, he didn’t receive the necessary stress doses of steroids for some reason. This, along with other causes, may have contributed to his death.”

Fueled by love

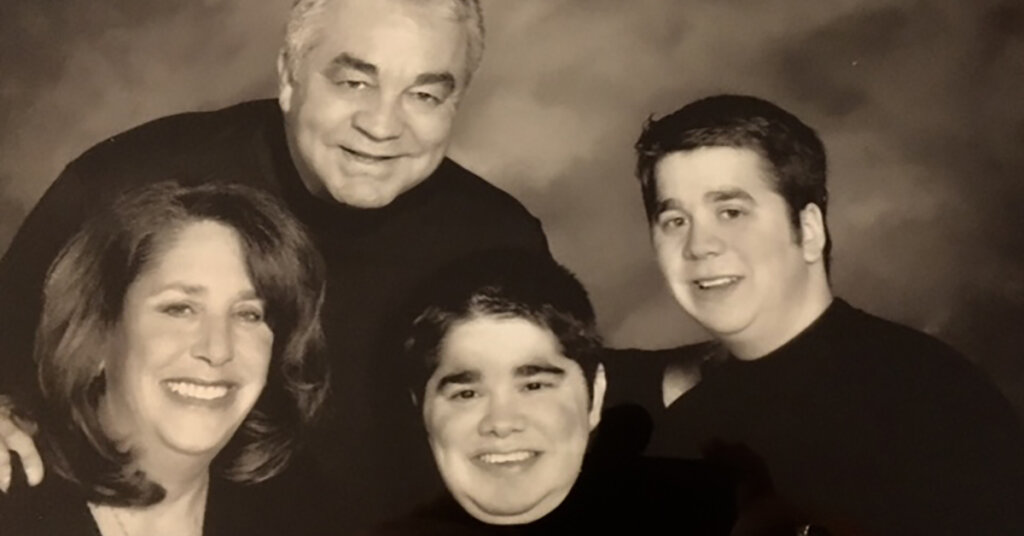

The Nicholoff family — Brian, his wife, Barbara, and their son Justin, now 34, who has a mild form of DMD — decided to use their experience to help others who are vulnerable in emergency situations because of their corticosteroid treatment, like PJ was.

Along with PJ’s primary physician, his family worked with the hospital where PJ had his surgery and with Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy (PPMD), assembling a group of neuromuscular disease experts to write and review PJ’s Protocol. It took 15 months.

When the protocol was released in 2015, word quickly spread on Facebook sites for PJ’s Protocol and the Jett Foundation, and on the MDA and PPMD websites. Articles about it landed on the pages of peer-reviewed medical journals. Brian also met with chief medical officers, and others at nursing and pharmacy organizations, and he spoke at conferences and webinars. PJ’s

Protocol has reached beyond the United States and is incorporated into DMD critical-care guidelines in the UK, Australia, Italy, and South America.

What you can do

PJ’s Protocol is accepted in the neuromuscular medicine community, and awareness of it is only growing. However, many healthcare providers in ERs and intensive care units may not know about it, since they often lack expertise in rare diseases, such as DMD and BMD. Individuals who are corticosteroid-dependent and their families should be prepared to advocate for themselves.

“A patient or family member can show PJ’s Protocol and say, ‘it’s in the medical literature, it’s been published, and it carries the stamp of approval from these organizations — and it pertains to my child in this setting,’” says Larry W. Markham, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at the MDA Care Center at Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis who has been involved in the multidisciplinary care of muscular dystrophy patients since 2001.

Here are four ways you can educate others about the PJ Nicholoff Steroid Protocol:

- Share the full protocol with your medical providers.

- Ask your medical institution if the protocol is part of their care guidelines. If not, advocate for it to be added.

- Print out MDA’s wallet-sized DMD Emergency Room Alert Card, and keep it with your health insurance card.

- Order PPMD’s weatherproof DMD Emergency Information Card to hang from a wheelchair or backpack.

Advocacy makes a difference

While MDA and many other organizations publicize the protocol and champion patient advocacy, medical advances in neuromuscular disease continue to charge ahead.

Dr. Markham has noticed that more patients and families are becoming involved with foundations and organizations to drive clinical care and research forward. “Patient advocacy has led to increased focus on proactive care for all DMD patients,” he says.

In addition, patients and their families are supporting research through funding or advocating for new areas of scientific inquiry. “Collectively, they’re making the case to industry, saying, ‘You can make progress here,’” he says. “There are any number of clinical trials of DMD drugs up for FDA approval, the biggest area of Duchenne research being gene therapy. That’s the result of advocacy.”

This gives the Nicholoff family hope in the face of their hurt. “When you lose your child so young, you never really bury them, but you learn to live with it.” Brian says. “Not a day passes that I don’t think of or do something about PJ’s Protocol, because I know it’s helping people. And PJ lives on because of that. That’s what makes me smile when I think of my son.”

[CTA]

Got questions about Duchenne muscular dystrophy? Read MDA’s DMD FAQ. Find more educational materials at mda.org/education.