Multifocal acquired motor axonopathy (MAMA) is an extremely rare neuromuscular disease that is often misdiagnosed as ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) due to similarities in the symptoms that initially occur in affected individuals. MAMA typically begins as weakness in the hands and arms, although it can also sometimes develop first in the feet or legs. Over time, the weakness can progress or worsen; however, unlike ALS, MAMA progresses slowly and does not typically result in shortened life span, although it can lead to significant disability. MAMA occurs more often in men than in women.

Although the exact cause for the disease is unknown, it’s suspected that MAMA may be an autoimmune disease, meaning the individual’s immune system attacks the body’s own tissues. In MAMA, it’s believed that the immune system attacks the motor neurons, which are nerve cells that control the muscles. When motor neurons cannot function properly, the muscles that they control become weak and then nonfunctional. Many individuals affected by MAMA respond to a treatment called intravenous immunoglobulin, or IVIg, which is thought to work by dampening the individual’s immune system and slowing the progression of the disease.

MDA funds research on several diseases affecting motor neurons such as ALS, spinal muscular atrophy and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, and gaining a better understanding of how motor neurons function and stay healthy may also lead to a better understanding of MAMA. MDA also supports research on myasthenia gravis (MG) which, like MAMA, is also an autoimmune disease, so learnings from research into the disease processes of MG and therapeutic strategies for the disease could also potentially be helpful to scientists studying MAMA.

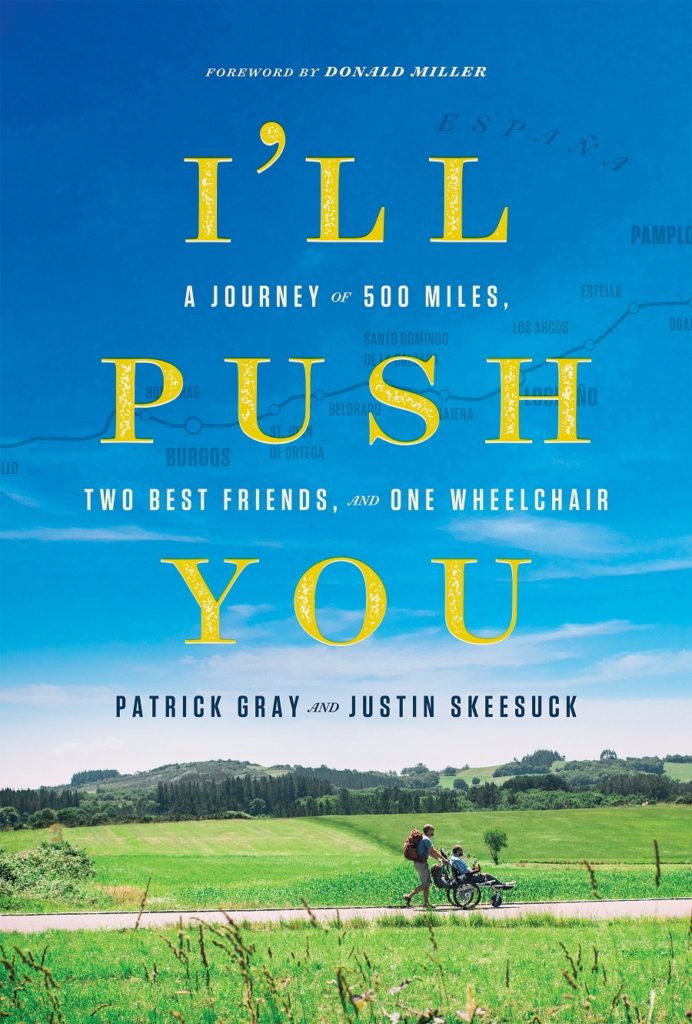

Justin Skeesuck, who shared his experience of being pushed in a wheelchair by his best friend Patrick Gray 500 miles on the Camino de Santiago in the book and film I’ll Push You, lives with MAMA. Originally diagnosed with ALS and given four years to live, Justin and his doctors cycled through several more diagnoses before landing on MAMA. He wrote about that diagnostic experience in his book, an exclusive excerpt of which MDA is sharing here. To continue reading Justin and Patrick’s story, you can purchase I’ll Push You wherever books are sold.

Answers and Questions

Answers and Questions

How many hours have I spent in the waiting room of a doctor’s office over the past thirteen years? I’ve lost count. During that time, I’ve endured an unending series of muscle biopsies, MRIs, blood tests, and various other forms of poking, probing, and prodding. And still no diagnosis I can depend on.

When I was in high school, my best friend, Patrick Gray, used to come with me to a lot of my appointments, but the distance between his home in Idaho and mine in Southern California makes that a little difficult now. Since moving to San Diego, I’ve often sat here alone, waiting for answers. Today, I’m grateful that my wife, Kirstin, is able to be with me.

The door leading back to the exam rooms opens, and Jennifer, my doctor’s medical assistant, surveys the busy waiting room. We make eye contact, and even though she knows Kirstin and me well, she goes through the formality of calling my name.

“Justin Skeesuck, come on back.”

By the time I get to my feet, with my leg braces and cane keeping me upright, Kirstin is already at the door. She knows I want to get there on my own, even if it takes me a while. As we continue down the hall, Kirstin and Jennifer slow their gait to allow me to keep up.

“I like your cane, Justin,” Jennifer says as we approach the exam room. “Is it new?”

I look down at the dark purple wood. “Yeah, my best friend made it for me.”

“It’s beautiful.”

When the weakness spread from my left leg to my right, Patrick purchased a four-foot slab of purpleheart wood and spent hours in his garage with a jigsaw and hand sanding tools, fashioning a beautiful cane. It has become a cherished symbol of our lifelong friendship.

“The doctor will be with you in a few minutes,” Jennifer says as my wife and I take our seats. Smiling, she closes the door softly.

Kirstin has come prepared for the wait. She pulls a magazine out of her purse and begins to thumb through the pages to pass the time. I settle into my chair, lean my head back against the wall, and close my eyes as time seems to stand still.

“It’s taking longer than normal,” Kirstin says after a while, as she replaces the magazine in her purse.

“There were a lot of people in the waiting room today,” I reply. “I’m just hoping that when he gets here he has some answers this time.”

For years, my team of neurologists has struggled to identify what exactly is going on in my body. Though my symptoms are similar to those of some well-known diseases—such as ALS—they don’t perfectly align with any of them. We’re hoping this latest round of tests, blood work, and muscle biopsies will bring a breakthrough—anything that will give me some insight into what the future might hold.

I would be satisfied at this point just to have a name for what I have. My team of physicians has gone through four diagnoses so far, and all have proved to be incorrect. Whatever I have is so rare, they aren’t sure it even has a name.

The doctor finally walks in and takes a seat on the rolling stool. His white lab coat hangs loosely over a tweed sport coat, and his salt-and-pepper hair is combed neatly. He glances at my chart in his hands and looks at Kirstin and me through his large, metal-rimmed glasses.

“Hey, guys, how are you doing today?” he says with a faint hint of a smile.

“Hoping for some answers,” I reply with a chuckle, “but expecting more questions.”

“Fair enough. Well, today we have a little bit of both.”

Never one for chitchat, he quickly begins his exam. Working his way from head to toe, he checks my eyes, listens to my heart and lungs, checks my blood pressure, tests my reflexes, and probes for any pain in my joints. He finishes the exam by testing my hand strength to make sure the weakness hasn’t spread.

Seemingly satisfied, he says, “Let’s head down the hall.”

We follow him, as we have dozens of times before, to finish my appointment in the quiet of his office, a surprisingly small space filled with a large desk in the center surrounded by walls of bookshelves full of medical journals and books with names I can’t pronounce. His diploma from Harvard and several framed awards have a prominent place on the wall.

“We’ve never been more certain of a diagnosis than we are now,” he says as he settles into his desk chair and we sit down across from him.

“All right,” I say. “Does it have a name?”

The doctor’s face tightens almost imperceptibly. “We’re pretty certain you have what is called multifocal acquired motor axonopathy. Or MAMA for short.”

“What exactly is it?” Kirstin asks.

“It’s similar in many respects to ALS. Which is why Justin was misdiagnosed the first time around.”

Turning to me, he continues, “Your immune system is attacking your nervous system, and your motor nerves are shutting down. This disease doesn’t affect your sensory nerves, just your ability to move. Normally, it hinders limited portions of a person’s body, but in your case, it has attacked everything from your waist down. That’s one of the reasons you’ve been so difficult to diagnose. MAMA typically starts in the hands. To see it affect such a large portion of the body is quite rare.”

My wife leans forward and grabs my hand. “Will it get worse? Do we know how long we have?”

“Like I said, we have both answers and questions today . . .”

He pauses for a moment before continuing.

“It will get worse over time. To what degree, we still aren’t sure.”

“So, what’s the deal?” I ask.

“It’s likely this disease will result in complications that will lead to your death.”

Kirstin takes a slow, deep breath as her eyes well up with tears.

This isn’t the first time I’ve been told I’m going to die. When I was originally diagnosed with ALS, the doctor told me I had four years to live. That was nearly nine years ago. This time there’s no known life expectancy, but the prognosis feels different; it feels more real.

“Do we know what causes it?” I ask.

“Well, we don’t know precise cause and effect, but sometimes traumatic events can trigger certain diseases.”

He pauses again to gather his thoughts and then continues. “Our best guess is that the disease was dormant throughout your childhood, and that it may have been awakened by your car accident.”

“What?”

That accident was thirteen years ago.

***

It was a crisp, clear spring morning in April 1991, but I remember it like it was yesterday. The brilliant blue sky over my hometown of Ontario, Oregon, was devoid of clouds, and the rising sun sat low, just above the horizon to the east, making silhouettes of the mountains as I stepped outside my front door to wait for my friend Jason to pick me up for a basketball tournament that was scheduled to start in less than an hour.

“Where is he?” I wondered aloud. “We’re going to be late.”

As if on cue, Jason rounded the corner in his small, dark red 1987 Toyota pickup. I poked my head back inside the house to say good-bye to my parents before walking out to the driveway, where Jason was now waiting.

A few months shy of my sixteenth birthday, I was still too young to drive, but Jason had recently gotten his license, and he was eager to get his well-traveled truck out on the freeway. As I fastened my seatbelt across my chest and lap, I looked over at Jason. His lap belt was secure, but the shoulder strap was hanging loose.

“You should probably get that fixed,” I said with a raised eyebrow. Jason just smiled and put the truck in gear.

In a matter of minutes, we were on I-84, headed east toward Northwest Nazarene College in nearby Nampa, Idaho. Even with our sunglasses on, the rising sun made us squint as it filled the gap between the pickup’s sun visors and the mountains in the distance. Because we were running late, Jason put some extra weight to the gas pedal.

As the sun climbed a little higher in the sky, the glare from the east intensified. At 80 mph, Jason was doing his best to get us to the gymnasium on time. But the faster he went, the more noticeable the poor alignment of his truck became.

As I leaned forward to find some good music on the radio, the twist of the dial was interrupted by a loud thump, thump, thump from under my feet.

Looking up, I saw we had drifted hard to the right and both passenger-side tires were off the edge of the asphalt, bouncing through the dirt, gravel, and tufts of grass on the poorly maintained shoulder. As Jason struggled for control, I could see we were rapidly approaching a concrete support pillar of an overpass.

“Jason, look out!”

He jerked the wheel hard to the left, trying to get us back onto the roadway, but overcorrected, sending the truck into a 180-degree spin. For a split second, we were facing west, with traffic speeding toward us—until we slid onto the median and began to roll. The explosive sound of metal on gravel filled my ears as the truck slammed against the ground. Everything happened so fast, I soon lost my bearings as we rolled across the median and caught some air.

It was a brief moment, but time stood still.

So many thoughts rushed through my head as the ground outside my window came at me in slow motion. When the passenger side of the truck collided with the ground one last time, the sound was deafening, and the impact reverberated throughout my body.

Is this how my life will end?

What will the paramedics tell my family?

What will my parents say to Patrick?

When the truck finally came to rest, I was suspended from my seat by my seatbelt and Jason was below me, with his upper body partially out the window of the driver side door, the door frame across his back. A small depression in the ground was all that kept the truck from crushing him.

Looking out through the fractured windshield, I could see multiple vehicles stopped in the distance and many people running toward us to help.

“Jason, are you alive?”

“Yes,” came his muffled reply, as his upper body was trapped between the truck and the ground below.

“I have to get out of here!” I yelled as I kicked at the windshield, but it wouldn’t budge.

Desperate to help my friend, I unbuckled my seatbelt and tumbled down on top of him. I heard him moan in pain.

“Get off me!” he said through gritted teeth.

I shifted my feet and straddled his body while pushing against the passenger door above me. It didn’t move. Somehow, though, I was able to wiggle my way out through the slider in the rear window.

As my feet touched the ground, several people approached me. I shouted, “My friend is still trapped! He needs help!”

Someone yelled, “Let’s see if we can get the truck back on its wheels.”

With a collective effort, the assembled onlookers were able to heave the truck up high enough for Jason to pull himself back into the cab and release his seatbelt. As they continued to hold the truck off the ground, Jason was able to crawl out the driver’s side window.

Somehow, I walked away from the accident with only a few scrapes and bruises. Jason wasn’t as lucky. He ruptured some discs in his back. But considering the severity of the accident, his injuries could have been much worse.

Four months later, at the beginning of my junior year, I was running down the soccer field during a game when I noticed that my left foot wasn’t moving normally. I could plant and push off to make a cut, but I couldn’t raise my foot back up. No matter how hard I tried to control it, my foot would flop around. Sometimes the toe of my cleats caught the ground as I ran, causing me to stumble.

When I brought this to my parents’ attention, we began looking for answers. The problem seemed to be isolated to my foot, so we went to a podiatrist. He was completely stumped and referred us to a neurologist. The neurologist had no real answers, but he had a plaster cast molding made of my left foot, which resulted in a custom-fitted white orthotic brace made of lightweight plastic. This new support was a foot bed insert for my shoes that curved around my heel and snugly supported my calf. This brace provided the support needed to maintain a relatively normal level of activity.

For one of my fitting appointments, Patrick went with me.

As I stood up and took a few steps with the brace securely fastened across the front of my lower leg with a Velcro strap, the aluminum hinges on each side of my ankle squeaked.

“Dude! You can totally play the sympathy card with the ladies!” Patrick said with a laugh.

Raising my eyebrows, I replied, “Not a bad idea!”

“How does it feel?” he asked as I walked around the doctor’s office.

“Better than dragging my foot.”

“I kind of like you dragging your foot,” he said, chuckling to himself. “Makes me look better!”

“You’re an idiot,” I said, laughing out loud.

“Seriously though, you’re moving pretty well. I can barely see a limp.”

Running a few steps, I felt my confidence rising. “Yeah! It feels great. I think I can still play tennis with no problem.”

With this new support system, I took up my racket and played both my junior and senior years. I kept close tabs on the weakness in my foot, and it seemed the worst was over. But not long after graduation, I could feel it spreading to more muscles in my lower leg.

***

I’d never made the connection between the weakness in my legs and the accident—until now. Kirstin is still sitting quietly next to me, holding my hand tightly. I’m squeezing hers so hard I can feel her pulse against my palm. So many thoughts are racing through my mind.

Turning to me, my wife says, “You need to call Patrick.”

Taken from I’ll Push You by Patrick Gray & Justin Skeesuck. Copyright © 2017. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved.