Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a chronic neuromuscular disease characterized by muscle weakness that worsens after activity and improves after rest. MG is caused by an autoimmune reaction in which the body’s immune system attacks its own tissues, interrupting the connection between nerves and muscles (the neuromuscular junction). MG can occur at any age and affects about 14-20 people in 100,000 in the United States (US). While there is currently no cure for MG, the symptoms of MG can be well-controlled with treatment and most people with MG can experience a high quality of life.

Symptoms of MG

MG affects both men and women, commonly occurring in women younger than 40 years old and in men older than 60 years old. MG usually begins in adulthood, but can occur in children.

People with MG typically experience weakness and fatigue of the body’s voluntary muscles (muscles that control purposeful movement). While symptoms can vary greatly between different people with the disease, MG often specifically affects the muscles that control movement of the eyes (extraocular muscles) and eyelids, causing “ocular” weakness. As a result, some of the earliest symptoms of MG include partial paralysis of eye movements (ophthalmoparesis), double vision (diplopia), and droopy eyelids (ptosis).

MG presents in two main forms:

- Ocular MG: Weakness is limited to the eyelids and extraocular muscles

- Generalized MG (gMG): Weakness may affect ocular muscles, but also involves a combination of bulbar (e.g., tongue, jaw, throat), limb (e.g., arm, leg), and respiratory (e.g., diaphragm) muscles

More than 50% of people with MG present with ocular symptoms. Of those who have ocular symptoms, approximately half develop gMG within two years. Currently, there is no way to predict whether a person with ocular MG will develop gMG.

In people with gMG, muscle weakness typically spreads from the face and neck to the upper limbs, the hands, and then the lower limbs. Affected people may experience difficulty lifting their arms over their head, rising from a sitting position, walking long distances, climbing stairs, or gripping heavy objects.

Weakness and fatigue in the neck, jaw, and throat can also occur early in MG. This pattern of weakness is known as “bulbar,” because it relates to the nerves that originate from the bulb-like part of the brainstem. About 15% of people with MG present with bulbar symptoms, which can cause difficulty with talking (dysarthria), chewing, swallowing (dysphagia), and holding up the head.

Though it is highly uncommon, about 5% of people with MG experience only limb weakness, without ocular or bulbar symptoms.

A prominent feature of MG that distinguishes it from other diseases with muscle weakness is the fluctuating nature of the weakness, along with muscle fatigue (loss of muscle power/force) over time. The degree of muscle weakness experienced by a person with MG may vary over hours, from day to day, or over weeks or months. Furthermore, the weakness will typically worsen with regular muscle use and often later in the day, while improving with rest or upon awakening. Early in the disease course, some people with MG may experience alternating periods in which symptoms subside (remissions) or worsen (exacerbations), with exacerbations sometimes triggered by external factors such as infection, severe stress, or excessive physical activity. As MG progresses, however, the symptom-free periods become more infrequent. In the majority of people with MG, the maximum extent of the disease is seen within two or three years after symptom onset.

For more information about the signs and symptoms of MG, an overview can be found here.

MG in children and infants

Although MG typically affects adults, it may occur in children in rare cases. Approximately 10-15% percent of MG cases in North America occur in children below the age of 18 (autoimmune juvenile MG).

MG can also affect infants. In a temporary condition known as neonatal MG, a mother with MG transfers some autoimmune components to the growing fetus, leading to MG symptoms following birth. These symptoms typically resolve in the first weeks to months of the baby’s life.

Another condition, congenital myasthenia, produces an MG-like disease in infants, but is not caused by autoimmunity. In congenital myasthenia, a defective gene disrupts the neuromuscular junction, resulting in symptoms similar to ones observed with MG.

Complications of MG

MG is not typically life-threatening. In rare cases, however, weakness may spread to muscles that control breathing. This can result in the most serious symptoms in MG, respiratory insufficiency and pending respiratory failure, also known as “myasthenic crisis.” Myasthenic crisis can occur spontaneously or may be triggered by factors such as surgery, infections, or certain medications.

Causes of MG

MG occurs spontaneously for unknown reasons. People with MG have an increased frequency of having other autoimmune diseases, and a small percentage may also have family members with MG. Some gene variants have been linked to a predisposition to MG, but a causative gene has not been identified. It is likely that a combination of a genetic predisposition and triggering environmental factors cause MG.

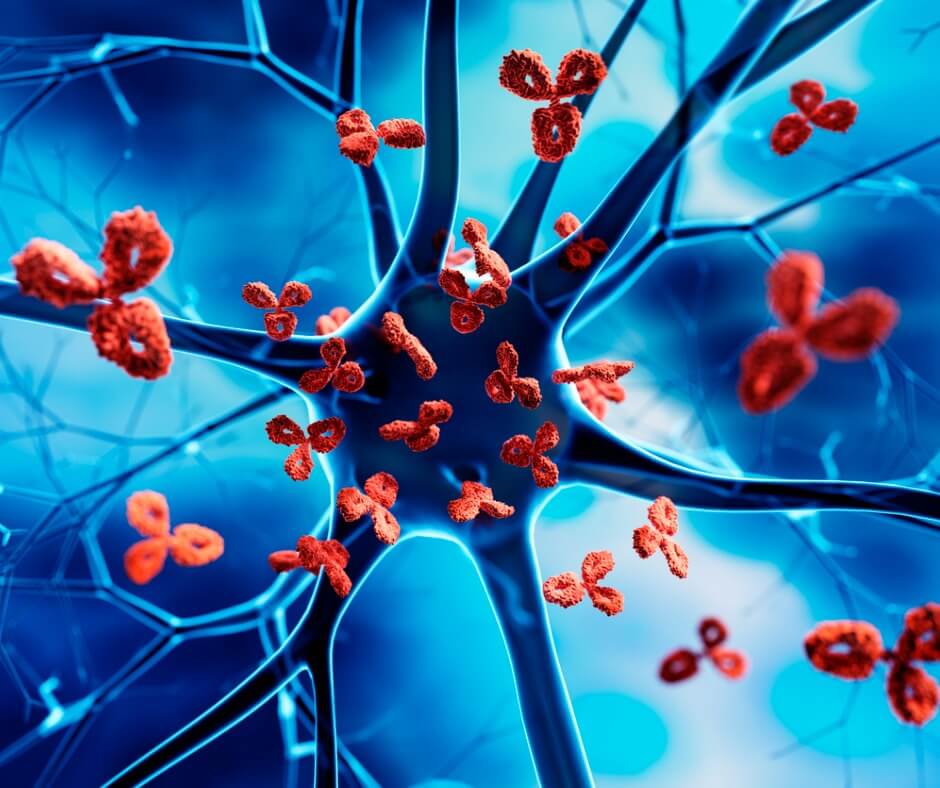

MG results from an autoimmune response in which components of the body’s immune defenses (i.e., antibodies) inappropriately attack and damage certain receptors on muscle cells, thereby disrupting their ability to communicate with nerve cells. The cause of this autoimmune response in people with MG is unknown. Researchers think that a defect in the part of the body known as the thymus (an organ located behind the breastbone), which plays an important role in making and training the cells of the immune system, could contribute to MG. One theory is that that the thymus of people with MG may not appropriately eliminate the immune cells that produce antibodies that attack body tissues.

Abnormal antibodies found in MG

About 80-90% of people with MG have abnormal antibodies in their blood serum that attack the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) on muscle cells. These people are known as being “seropositive” for antibodies to AChR. Normally, AChR recognizes a chemical signal released from nerve cells that instructs muscle fibers to contract. In people with AChR MG, the autoimmune response to AChR decreases the number of acetylcholine receptors. This causes failed nerve-to-muscle communication and leads to weak muscle contractions.

Some people with MG who do not have antibodies to AChR have antibodies that attack another protein, muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinase (MuSK). MuSK MG represents about 4% of all people with MG. The abnormalities that lead to production of antibodies to MuSK are poorly understood, but unlike in AChR MG, are not thought to involve the thymus.

A few additional abnormal antibodies have been identified in some people with MG (e.g., antibodies to LRP4), but these less common forms of MG are poorly understood. A small percentage of people with MG do not show abnormal antibodies to any known targets, and are designated as having “seronegative” MG.

Knowledge of the abnormal antibodies that contribute to MG helps in diagnosing people with the different forms of MG.

Current management of MG

Modern therapies have considerably improved the prognosis for people living with MG. The goal of management in MG is to decrease symptoms to their lowest point, while minimizing side effects from medications. The primary therapies used to treat MG are:

Symptomatic treatment:

- Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors – Increase nerve-to-muscle communication

Disease modifying treatments:

- Corticosteroids (e.g. prednisone) – Inhibit the immune system

- Non-steroid Immunosuppressants (e.g. mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine) – Modulate the immune response

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) – Introduces normal antibodies into the blood

- Plasma Exchange/Therapeutic Apheresis – Filters out abnormal antibodies from the blood

- Complement Inhibitors (e.g. eculizumab, ravulizumab) – Block an immune pathway that contributes to disease

- Neonatal Fc receptor inhibitor (e.g. efgartigimod) – Helps to eliminate abnormal antibodies

- Thymectomy – Removes the defective thymus

Treatment decisions for MG are based on the specific symptoms and disease course experienced by each person with the disease. With the current availability of treatment options, three stages of the disease are commonly reported by clinicians:

- An active phase with fluctuations and the most severe symptoms in the first five to seven years after symptom onset. Myasthenic crisis is most likely to occur in this period.

- A more stable phase, in which symptoms are stable but persist. Symptoms may worsen with infection, reducing medication dosage, or other changes.

- For many people, remission, either on or off therapy.

A complication of MG management is that many medications can increase weakness and should be avoided or used with caution. Resources are available to learn more about cautionary drugs for people with MG, and it is important to check with a doctor before beginning new medications.

MG is chronic, but treatable, and many people with MG can achieve long-term remission of symptoms and a high quality of life.

Evolving research and treatment landscape

Research advances and the promise of better therapeutics on the horizon offer the hope of improved disease management for people living with MG.

Researchers are currently investigating new therapeutic strategies to counter the autoimmune responses that cause MG, including development of “monoclonal antibodies” that can deplete the immune cells that produce abnormal antibodies. The use of thymectomy to address MG is also being studied to better understand the optimal uses and limitations of this procedure. Another active avenue of research is the search for biomarkers that can help diagnose MG earlier or predict the course of disease.

To learn more about clinical trial opportunities in MG, visit clinicaltrials.gov and search for “myasthenia gravis” in the condition or disease field.

MDA’s work to further cutting-edge MG research

Since its inception, MDA has invested more than $56 million in MG research, with nearly $1 million spent on MG-specific research grants in the last five years (2017-2021). MDA funding has helped to support foundational research underlying development of targeted therapies for MG, including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs eculizumab, efgartigimod, and ravulizumab.MDA’s Resource Center provides support, guidance, and resources for patients and families, including information about myasthenia gravis, open clinical trials, and other services. Contact the MDA Resource Center at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 or ResourceCenter@mdausa.org